One of the reasons I have always admired the Red Studio by Matisse, is that, for me it is one of the first modernist paintings.

The red studio. Henri Matisse 1911

It is a painting that really does leave the idea that we look through a window (frame) to observe something in front of us that is external to the self, behind.

It is not just that Matisse uses colour in such a masterful way, or that the composition is a reflection of his drawing skills, it's that he bought everything (objects and the room) up to the physical surface of the painting (the picture plane). It is this which makes it is such an innovative painting and influenced the direction that contemporary art would take.

Below is a definition which explains what the picture plane is:

"In traditional illusionist painting using perspective, the picture plane can be thought of as the glass of the notional window through which the viewer looks into the representation of reality that lies beyond. In practice the picture plane is the same as the actual physical surface of the painting.

In modern art the picture plane became a major issue. Formalist theory asserts that a painting is a flat object and that in the interests of truth it should not pretend to be other than flat. In other words, there should be no illusion of three dimensions and so all the elements of the painting should be located on the picture plane."

Tate Gallery London.

Still life with oranges and apples. Paul Cézanne 1895-1900

Matisse admired the work of Paul Cézanne.

"Look at Cézanne: never an uneven or weak spot in his pictures. Everything has to be bought within the same picture plane in the painter's mind."

Matisse.The Master. Hilary Spurling. 2005 P.80

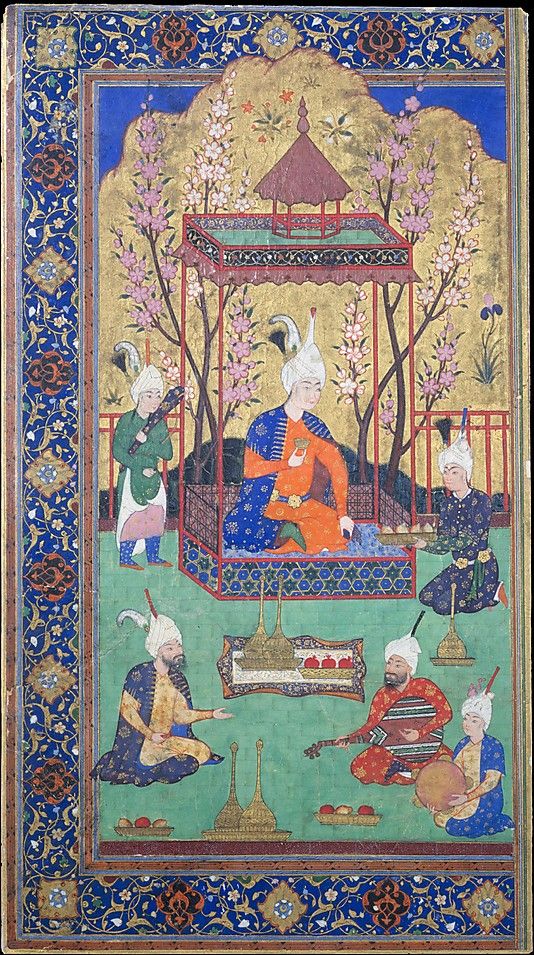

Munich 1910 exhibition of Persian miniatures and carpets.

Matisse visited this exhibition and noted that:

"the Persian miniatures showed me the possibility of my sensations. That art had devices to suggest a greater space, a really plastic space. It helped me to get away from intimate painting." Matisse on Art. Jack Flam. 1995 P. 178

Matisse on Art. Jack Flam. 1995 P. 178

The 'plastic' elements of a painting are: Line, shape, form, space, texture, tone (value) colour and I would add time.

Prince in garden courtyard. Persian illuminated manuscript 1525-1530

It is this realisation that set Matisse free to follow his own expression, to state whether something should exist in his work through the juxtaposition of the plastic elements of a painting, time and space. In this way painting would become an individual expression rather than a depiction of an external representation that, in any case, can never be 'real'.

Homage to Matisse. Mark Rothko 1953

Mark Rothko (1903-1970)

Mark Rothko, original name Marcus Rothkovitch, American painter whose works introduced contemplative introspection into the melodramatic post-World War II Abstract Expressionist school; his use of colour as the sole means of expression led to the development of Colour Field Painting. In 1913 Rothko’s family emigrated from Russia to the U.S., where they settled in Portland, Ore. During his youth he was preoccupied with politics and social issues. He entered Yale University in 1921, intending to become a labour leader, but dropped out after two years and wandered about the U.S. In 1925 he settled in New York City and took up painting. Although he studied briefly under the painter Max Weber, he was essentially self-taught.

Rothko first worked in a realistic style that culminated in his Subway series of the late 1930s, showing the loneliness of persons in drab urban environments. This gave way in the early 1940s to the semi-abstract biomorphic forms of the ritualistic Baptismal Scene (1945). By 1948, however, he had arrived at a highly personal form of Abstract Expressionism. Unlike many of his fellow Abstract Expressionists, Rothko never relied on such dramatic techniques as violent brushstrokes or the dripping and splattering of paint. Instead, his virtually gestureless paintings achieved their effects by juxtaposing large areas of melting colours that seemingly float parallel to the picture plane in an indeterminate, atmospheric space.

Rothko spent the rest of his life refining this basic style through continuous simplification. He restricted his designs to two or three “soft-edged” rectangles that nearly filled the wall-sized vertical formats like monumental abstract icons. Despite their large size, however, his paintings derived a remarkable sense of intimacy from the play of nuances within local colour.

From 1958 to 1966 Rothko worked intermittently on a series of 14 immense canvases (the largest was about 11 × 15 feet [3 × 5 metres]) eventually placed in a nondenominational chapel in Houston, Texas, called, after his death, the Rothko Chapel. These paintings were virtual monochromes of darkly glowing browns, maroons, reds, and blacks. Their sombre intensity reveals the deep mysticism of Rothko’s later years. Plagued by ill health and the conviction that he had been forgotten by those artists who had learned most from his painting, he committed suicide.

After his death, the execution of Rothko’s will provoked one of the most spectacular and complex court cases in the history of modern art, lasting for 11 years (1972–82). The misanthropic Rothko had hoarded his works, numbering 798 paintings, as well as many sketches and drawings. His daughter, Kate Rothko, accused the executors of the estate (Bernard J. Reis, Theodoros Stamos, and Morton Levine) and Frank Lloyd, owner of Marlborough Galleries in New York City, of conspiracy and conflict of interest in selling the works—in effect, of enriching themselves. The courts decided against the executors and Lloyd, who were heavily fined. Lloyd was tried separately and convicted on criminal charges of tampering with evidence. In 1979 a new board of the Mark Rothko Foundation was established, and all the works in the estate were divided between the artist’s two children and the Foundation. In 1984 the Foundation’s share of works was distributed to 19 museums in the United States, Great Britain, the Netherlands, Denmark, and Israel; the best and the largest proportion went to the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Once he had arrived at his mature style of painting in 1949 Rothko rarely titled his works. His simple formula of 'breathing' paint into a sequence of feathery-edged rectangular fields of pure color bespoke a world of emotion and feeling beyond the everyday realm of objects, names or things. Striving for the transcendent by invoking a sense of the sublime, Rothko's paintings were not, as he famously said, 'pictures of an experience,' they 'were an experience'. His paintings therefore had little need for names, titles or descriptive explanations.

As the title Rothko gave to this work suggests, Homage to Matisse is a rare exception. It was painted in 1954, the year of the great French painter's death and it is equally rare in that it is a public declaration by Rothko of the debt he owed to another, and in particular, European artist. Like many artists of the New York School Rothko was often wary of allowing his work to be seen as in any way indebted to the then all-powerful French tradition in painting. Wishing to be seen as an independent artist and originator in his own right, Rothko was also ideologically opposed to the so-called "School of Paris" for what he saw as its lack of moral and political conscience in an age of profound crisis. Indeed the students he taught in California in the late 1940s remember him and Clyfford Still "yak, yak, yakking against the French tradition" and William Rubin has recalled that throughout his life Rothko "was always anxious lest he should be taken for a painter in the vein of Matisse, whom he nonetheless dearly loved" (cited in Anna Chave, Mark Rothko, Subjects in Abstraction New Haven 1989, p. 57, and W.Rubin, "Mark Rothko 1903- 1970", New York Times, 8 March 1970).

For Rothko to publicly declare a "Homage to Matisse" was consequently no small matter for the artist even though by 1954 Rothko was well established as one of the leading artists of his generation. It was also fitting. More than any other single artist, it was Matisse's example that had informed much of the direction as well as the ultimate liberation of Rothko's art between 1930 and 1949. In the 1920s Rothko had enrolled himself in the class of Max Weber a former pupil of Matisse's short-lived art school in Paris and in the 1930s Rothko shared a close friendship and working relationship with Milton Avery who, responding to Matisse's example, had inspired Rothko with his landscapes and female figures flattened into lyrical expanses of opaque colour. Essentially though it was Matisse's example and in particular, paintings like his Red Studio of 1911 that had given Rothko the courage to pursue his great breakthrough of 1949 when the representational forms, objects and symbols of his art finally disappeared and dissolved into his now familiar rectangles of pure non-objective color. The Red Studio was acquired by New York's Museum of Modern Art in the late 1940s and was first permanently installed in the museum in 1949. As Rothko told Dore Ashton, soon after the painting went on show he would repeatedly "spend hours and hours" sitting in front it. "When you looked at that painting," he said, "you became color, you became totally saturated with it" as if it were music (Rothko cited in J. E. B. Breslin Mark Rothko : A Biography, Chicago 1993, p. 283).

Rothko's own 'heroifying" of color, transforming it into the sole subject and drama of his art and his attempt to make it a direct experience for the viewer in the same way as music is clearly owed much to his understanding of Matisse's work and the elder artist's similar pursuance of an "inner vision" and his search through color for what he described as an underlying "essence". In a statement that parallel's much of Rothko's thinking, Matisse had declared in 1908 that "underneath this succession of moments which constitutes the superficial existence of beings and things and which is continually modifying and transforming them, one can search for a truer, more essential character" (Henri Matisse cited in D. Ashton, op cit).

Both Rothko and Matisse were responding to the essentially Symbolist idea that there is a direct and ultimately transcendent correspondence between color, sound, sensation, feeling and memory. It is an idea that, as Dore Ashton has pointed out, was perhaps best expressed by Stephan Mallarmé whose poetry Matisse declared he, almost religiously used to read each morning ' as one breathes a deep breath of fresh air.' Mallarmé Ashton writes, "had told himself as a youth that he must purify language and use it so that it could 'describe not the object itself but the effect it produces.' He spoke of a "spiritual theatre " and an "inner stage" where absences (equivalent to the [blank unpainted] whites Matisse employed [in the Red Studio] evoked his inner drama" (ibid).

These notions effecting a "pure" language beyond the imagery and objecthood of phenomenal reality--of a "drama" that spoke directly to the "inner" being of the viewer--were of course shared by Rothko, though Rothko articulated these same ideals in ways that were often phrased within the context of his own great influences such as Nietzsche, Greek tragedy, Shakespeare and Mozart. "Free of the familiar," Rothko declared in his appropriately titled text The Romantics were Prompted, "transcendental experiences become possible pictures must be miraculous a revelation, an unexpected and unprecedented resolution of an eternally familiar need." The "artist's real model", he asserted, is an ideal which embraces all of human drama" (Mark Rothko "The Portrait and the Modern Artist" broadcast with Adolph Gottlieb, Art in New York, WNYC, October 13, 1943, published in Adolph Gottlieb: A Retrospective New York, 1981, p. 170.).

That Matisse's work approached this "essence" or "ideal" by moving beyond phenomenal reality--painting as he often declared, not "things" but "the difference between things"--made him in Rothko's eyes what he described to Irving Sandler as "the greatest revolutionary in modern art". According to Sandler and somewhat typically Rothko immediately followed this statement of admiration with a clear disassociation between his own work and that of Matisse's, stating that he himself was "no colorist" and that morally he wished his art to be completely disassociated from that of all such "hedonistic painters" (Rothko cited in A. Chave, op.cit p. 57).

Executed at the height of what was arguably the most hedonistic and happy period of Rothko's career, in which the artist seems to have repeatedly revelled in a joyous and vibrant use of resonating color, Homage to Matisse is a clear, unashamed and unequivocal pictorial statement about the inherent similarities between the two artists' work. Consisting of a very simple scaffolding--three contrasting rectangles of strikingly different colour (red, yellow and blue)--the painting evokes a warm and joyous feeling. Tall and thin, the warmth simplicity and verticality of the work recalls the format of many of Matisse's balcony views onto the Mediterranean in which interior and exterior light and color radiate and interact in such a way that it appears that sunlight itself has become the subject of the painting.

Seeming to radiate a warm energy, the delicately brushed and feathery edges of the rectangles generate a hazy sense of shimmering light and heat. The deep rich calm of the lower blue rectangle contrasts strongly with the seemingly shifting and mobile transparent energy of the blended red and yellow rectangles at the top of the painting. In the magical transparent orange light generated by these two overlapping blocks of color, Rothko's masterful brushwork achieves an effect close to that of light pouring through a stained glass window. In establishing this effect, Rothko may have again been reminded of Matisse and in particular the stained glass windows he made for the chapel in Vence. This chapel was certainly in Rothko's mind a few years later when he contemplated his first series of mural paintings and it was also the primary motivation behind the Menils' later commissioning of Rothko to create a non-denominational chapel in Houston.

Using simple monolithic blocks of color to convey a pictorial drama that borders on the mystic, the powerful simplicity of this work demonstrates the radical new language of color that Rothko, at the same time as Matisse had done with his late cut-out paintings, had formulated in the early 1950s. In new and very different ways both artists were responding to the Symbolist belief that the simplest elements of painting, abstract color and form, could be used to speak powerfully and directly to the inner being and that in this way, they were creating approximations of the language of the human soul. As persuasive today as it must have been when it was first painted, Homage to Matisse is a fitting testament to this belief from one great artist to another.

Lot 34. Essay Christie's New York